The Forever Bond signifies a lasting emotional connection despite challenges, changes, or loss. This bond is not easily broken and often persists throughout a person’s life.

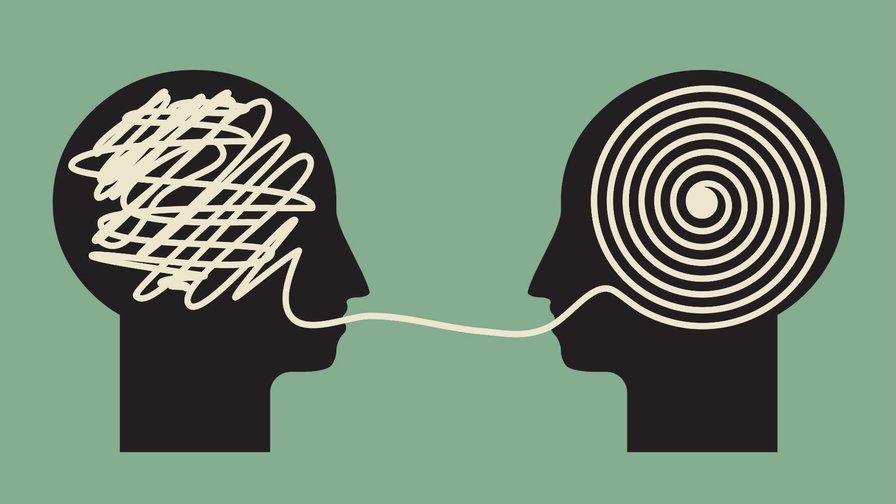

In "The Grieving Brain" by Dr. Mary Fridman O'Connor, the "Forever Bond" concept refers to the deep, enduring connections individuals form with their partners in marriage and other close relationships. This bond is characterized by emotional intimacy, shared experiences, and a profound sense of attachment.

The Forever Bond keeps the human race surviving through marriage, children, groups, relatives, and tribes. It is the glue that creates loyalty and holds groups together.

However, this same bond can also lead to profound grief, violence, destructive behaviors, and conflict when those bonds are attacked or forced to change.

When the primary relationship’s external lives change in status, as in divorce, the Forever Bond’s context is also forced to change, and it resists—especially with a spousal relationship or, more painfully, a child. It can feel like it is tearing you apart inside and out, with profound disappointment, broken promises, and confusion on a core level. You can feel like your emotional heart is breaking.

Understanding Helps

Understanding the grief process is crucial because it helps you better understand and accept what you are experiencing with more compassion and consideration. There is a way through, by yielding to what is needed to rewrite how the brain holds that kind of bond—the changed, new context—so even though the still bond lives, it learns to reflect your current reality of the change. Evidence shows the Forever Bond doesn’t quickly go away. This profound process affects the brain, nervous system, extended family, friends, and community. Humans usually have many Forever Bonds with multiple people in a lifetime. Grief is the mechanism that helps you deal with what Life brings you.

You don’t live on human terms. You live as a human on Life’s terms. No matter how hard you try to control Life, its terms win. Grief can help you be a more willing participant in Life’s terms: what is happening now outside your control, in small, slow steps taken often if you let it.

If You Let It

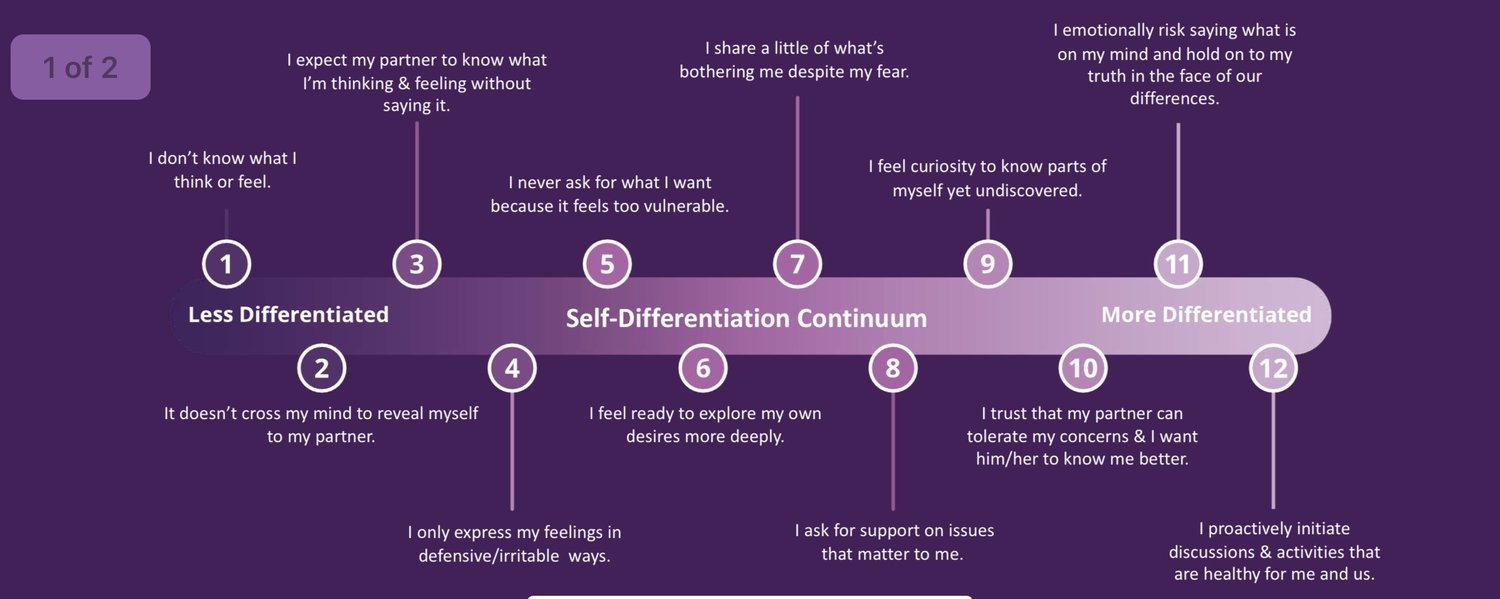

Rewriting or rewiring these Forever Bonds may seem slow, but there is so much to address, much of which you are even aware of. Therapy focused on Grief and the Forever Bond can enhance your brain’s acceptance, gradually. The grief process aims to bring you back from your past-based emotional and mental points of view to the present. This can allow you to focus on what is happening now rather than being blinded by the intensity of past hurts and continuing to try and change the other when they have moved on.

The felt Forever Bond often remains, though, somewhere deep in your emotional heart, allowing you to move on to new primary relationships, forming new Forever Bonds with others. Yeah. It is complicated.

While therapy cannot eliminate grief, it can help reduce the intensity of your resentment and regrets, which are the hardest parts to deal with. These unresolved feelings can trigger conflicts in the future, igniting marital and family disputes when you least expect it. The grief therapy process can help loosen the grip of these negative feelings and create space for healthier current relationships. If you you let it, on Life’s terms.

How You Will Know Grief Is Progressing

The Heavy Weight:

One of the ways to know when a grief layer is released? You will feel a little physically lighter. Unprocessed Grief is carried by thehe nervous system all over you have body and can feel like wearing a heavy weighted coat. That is also known as a burden. It often becomes normalized in order to function so the little moment of “feeling a little lighter” could mes as a surprise.

It Comes In Waves:

The emotions of Grief, once freed from emotional numbness, comes over you like an ocean wave. Some small, some large and some can drop you to your knees from the intensity. And, they can come seemingly out of nowhere. This is progress, though painful. The Forever Bond is working to change to a new relation contest, one small, slow step at a time. Over time, the emotional ways become further a part. A sign of more acceptance and adjustment. As long as the Forever Bond is deep in you, which is mist likely you whole life time, there are times that an emotional Grief wave can surface regarding that former relationship context.

More Grief Release Signposts:

Increased Acceptance

Understanding of Reality: You may begin to accept the reality of their loss rather than continually trying to deny or avoid it. They can acknowledge that the person, relationship or thing they lost is gone.

Integration of Loss: You start to integrate your loss into your life narrative, allowing yourself to move forward while still allowinh gratitude from what was lost and lessening the grip of resememrs and regrets.

Emotional Regulation

Decreased Intensity of Emotions: Intense feelings of sadness, anger, or anxiety may begin to lessen. You may experience more stable emotions and have greater control over your emotional reactions.

Ability to Experience Joy Again: The capacity to experience moments of happiness or joy without guilt or sadness may indicate progress. You may find pleasure in activities they once enjoyed.

Increased Engagement with Life

Reconnecting and creating new Social Circles: Individuals may start to reach out to friends and family, seeking social interaction and support rather than isolating themselves.

Pursuing Interests: A willingness to engage in hobbies, interests, or activities that were neglected during the height of grief can signify movement toward healing.

Improved Coping Mechanisms

Adopting Healthy Coping Strategies: you might develop healthier coping mechanisms, such as mindfulness, exercise, or creative outlets, rather than relying on avoidance or destructive behaviors.

Reflective Thinking

Meaning-Making: you may start to reflect on the experience of loss and find meaning or lessons learned from it. This reflective thinking can help you make sense of their grief.

Memorializing the Loss or the Deceased: They may engage in activities to honor or remember the person or relationship or thing you lost, such as creating a memory book, planting a tree, or participating in rituals.

Changes in Perspective

Shifts in Priorities: A change in life priorities or goals may occur, with you focusing more on what is meaningful to you following your loss.

Greater Empathy for Others: You may develop a deeper understanding of and empathy for others who are grieving, leading to increased compassion and connection.

Resilience

Increased Ability to Handle Challenges: you may find that you are better equipped to deal with other life challenges or stressors that arise, demonstrating emotional resilience.

Hope for the Future: An emerging sense of hope or willingness to plan for the future can signal progress in the grieving process.

Therefore:

Targeted therapy addressing grief, resentment, unexpressed emotions, and gratitude can ease your reactions to triggers from others and inside yourself is a way of loosening the grip of the past and free more emotional, mental and relationship space now. This can unstick other elements of your Grief process.

Your best friend in Life is you, with Compassion, Kindness and Mercy turned inward. Then, honesty. Yeah, Its complicated. And if you are a reading this, Life is Alive in you. Live on its terms.

Digging Deeper