Gottman Research

What To Do When Your Partner Doesn't Know How To Talk About Their Feelings

ON REPEAT: When You Tell The Same Troublesome Story Over And Over Again

The Adaptive Identity Model (A-I-M): How Your Brain Is Trying To Take Care Of You

How Your Brain Is Trying to Help Take Care Of You

(When You Are Willing To Work With It & Not Against It)

The Adaptive Identity Model (A-I-M)

By Don Elium, MFT

The Adaptive Identity Model (A-I-M). Your identity is not a fixed thing but a temporary framework your brain uses to navigate the world. This framework cycles through periods of stability, disruption, and renewal throughout your life. IT shows you how neuro-psychologically and biologically your self-identity and relationships are constantly in a state of natural adaptation and change.

In development by Don Elium, MFT, A-I-M synthesizes established principles from neuroscience, psychology, and biology to help you understand why we get stuck in old patterns and how to create new, more updated adaptive ones.

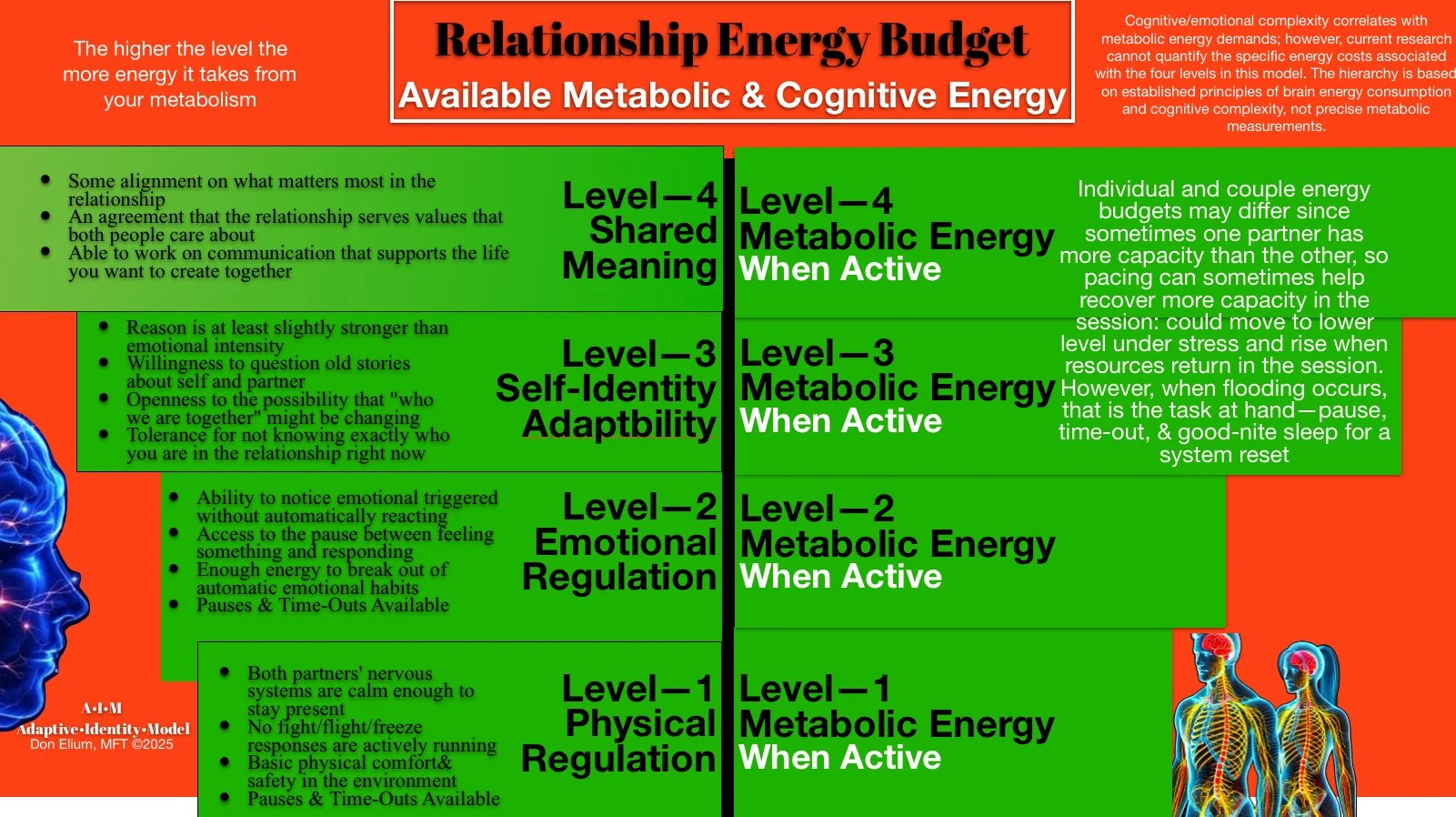

Your Brain’s Relationship Energy Budget: The Core Driver of Behavior

A central idea of the A-I-M model is that the brain is a highly energy-demanding organ. Although it makes up only 2% of your body weight, it consumes roughly 20% of your metabolic energy. Because of this, the brain’s number one priority is to be efficient and conserve energy. It achieves this by relying on two central operating systems for communication:

* System-1 (Sys-1): This is the brain’s fast, automatic, and low-energy mode. It uses familiar patterns and past experiences to respond quickly without having to think or analyze every situation from scratch. This system is a powerful survival tool and is easier to access under pressure.

* System-2 (Sys-2): This is the brain’s slower, deliberate, and high-energy mode. It requires significant metabolic energy to evaluate different viewpoints, process complex emotions, and actively seek accuracy. System-2 is harder to access under pressure and is what’s needed for thoughtful problem-solving.

When you are tired, hungry, or stressed, your brain defaults to the low-energy, automatic System-1, which often leads to predictable and recurring relationship conflicts.

The Pattern and the Story And Your Self-Identity

The A-I-M model explains that your brain doesn’t just store random facts; it organizes them into coherent narratives to create a stable sense of self. The “story” is the subjective, conscious narrative you tell yourself, and it is an emergence of an underlying neural “pattern”. This pattern is a heavily used neural pathway, like a deep groove in a hiking trail that your brain naturally follows because it’s more efficient than creating a new path. To your brain, the pattern and the story are not separate and are mutually influenceable.

These story patterns serve several key neurological functions:

Identity Maintenance: your Self-Identity Nueral Network reinforces and automates your self-identity patterns and a consistent sense of who you are in a relationship until these patterns become outdated due to life and people growth and changes and when the amount of energy it takes to keep them in action is greater than the energy it takes to update them, an updating process begins, whether you like it or not.

Meaning-Making Efficiency: your Self-Identity Neural Network, when flexible and has enough energy available, can form new points of view to address conflicts and create new personal meaning and shared relationship meaning from the changes that life demands create.

Emotional and Physical Regulation: Create a stable support for a more flexible and adaptive Self-Identity that can can support the emergence of Self-Awareness and can question rigid beliefs and adapt more productively to updated situations while the outdated points of view can soften and yield to the new.

Because these patterns are so efficient, your brain makes them feel automatic and real. This process is called identity crystallization, where a new story feels permanent, even though it is temporary. The brain helps you forget the struggle of creating this new version of your self-identity, making it feel like “who you’ve always been”.

The Cycle of Change: The Metabolic Tipping Point

Since life is constantly changing, the “new” story will eventually become outdated and no longer a good predictor of reality. The brain then has to expend more and more energy to maintain that old story in the face of new circumstances. The story only shifts when the cost of maintaining it exceeds the cost of creating a new one. This moment is called the metabolic tipping point.

Once this tipping point is reached, the brain enters a period of reorganization, and the old story begins to break down. This can feel confusing, unstable, and even scary, as your familiar sense of self is lost. This is the process of self-identity flexibility.

The Deeper Second Look: A Method for Conscious Change

The A-I-M model offers a process, the “Deeper Second Look,” to intentionally create a new story and its underlying pattern. This is not about using willpower to force change, which is energy-intensive and often fails. Instead, it is a compassionate, gentle, and repetitive process that works with the brain’s natural capacity for change.

The approach of gently and compassionate, slowly over an extended period of time with the phrase “I am becoming a person who...” is neurologically powerful because it doesn’t demand immediate, perfect transformation that your brain will detect as a threat and find ways to ignore or distract you away. A Deeper Second Look acknowledges the gradual development of adaptive neural pathways, which often takes an average of 66 days to become automatic. This small, consistent practice strengthens a new neural circuit until it becomes your brain’s new, energy-efficient default.

The change isn’t that you get one permanent new story; it’s that you have a new, healthier trail to follow, and a more adaptive story naturally emerges from it. An adaptive tale is more accurate, flexible, and aligned with your growth, freeing up mental energy participation with what is actually occurring now. By understanding and working with your brain’s energy budget, you can participate in this natural cycles of change in your relationships and your life.

For More Info contact Don Elium, MFT 925 26 8282 SF Bay Area

Gottman

https://open.spotify.com/episode/2xJ9DQTcJ4Sl6WHGhFF5ZU?si=SK2fz0tWREGLfJQiNWWYUg&context=spotify%3Ashow%3A1CfW319UkBMVhCXfei8huv

How Small Words Can Wreck Big Relationships

How Small Words Can Wreck Big Relationships

Narrative Over-generalization

By Don Elium, MFT

In every close relationship—whether marriage, family, or friendships—there’s a hidden villain: narrative over-generalization. You may not know the term, but you’ve heard its voice. It whispers through statements like, “You always do that,” or “You never listen to me.” These words are small, yet their impact can be immense, sparking defensiveness, resentment, and distance.

Narrative over-generalization occurs when we take specific incidents and unfairly expand them into sweeping judgments. It is a natural shortcut for our brain, simplifying complex realities into easy narratives—it can be dangerously misleading in close relationships. Our minds jump from “you forgot this one thing” to “you never care about what matters to me,” often without us noticing the shift.

Neurologically, this process is tied to the Default Mode Network (DMN), the brain’s primary storyteller. The DMN seeks to stabilize our sense of self and the world by quickly organizing experiences into neat, predictable categories. And that’s not all bad. It’s essential to survival. From an evolutionary perspective, generalizations once kept us alive. If the last time we touched a glowing orange object we got burned, the brain signals, Avoid glowing orange things—always. The DMN identifies patterns, builds mental shortcuts, and stores these as part of a self-protective archive. This internal narrative system is deeply efficient, aiding us in navigating by relying on familiar stories about who we are and what we expect from others.

But what helps us survive doesn’t always serve us in intimacy. In close relationships, the DMN’s elegant storytelling can turn against us. Instead of offering clarity, these generalized narratives can reinforce conflict, frustration, and emotional pain. The DMN means well—it’s trying to protect us from repeated harm. However, doing so may convince us that our partner is a threat when they’re human, flawed, and tired.

When we frequently use over-generalizations, our loved ones naturally feel misunderstood and attacked. Phrases like “You never appreciate me” trigger defensiveness because they challenge the person's core identity rather than addressing specific behaviors. The body hears these statements as accusations, not invitations. Over time, this habit can erode trust, leaving relationships mired in resentment. We stop seeing the person in front of us. We start seeing only the story we've rehearsed about them.

The key to changing this dynamic lies in gently reality-testing these generalized narratives. The DMN may supply the first draft, but we are not required to publish it as the truth. When we pause and scrutinize our assumptions, we often discover they’re incomplete or untrue. Your partner might sometimes overlook something important, but does that mean they never care? Is their forgetfulness really a reflection of disregard, or of their nervous system under stress, their focus elsewhere, their unspoken overwhelm?

Challenging your statements gently allows room for a new, healthier dialogue. Replacing broad statements like “always” and “never” with precise language transforms conflict into constructive conversation. For example, instead of saying, “You always interrupt me,” try stating exactly what you feel: “I felt interrupted just now, and I’d like to finish my thought.” This slight shift can dramatically lower defensiveness and build understanding. It signals: I’m talking about this moment, not your entire character.

Couples and families that consciously reduce narrative overgeneralization report greater relational harmony. Instead of feeling trapped by labels, each person can address actual issues, making them easier to solve. Rather than viewing conflicts as temporary misunderstandings instead of personal failures, they also start by exaggerating. This moment of awareness—this flicker of insight—is where true intimacy begins.

Recognizing and correcting narrative over-generalization offers practical therapeutic benefits. Clients learn tools to reframe their internal stories, moving from sweeping negative judgments to specific, solvable concerns. This practice significantly reduces conflict intensity and increases relationship empathy and emotional intelligence. It also rewires the DMN itself, nudging it toward more accurate and compassionate storytelling over time.

Changing the narrative isn’t about ignoring real issues but seeing each other. When we step away from black-and-white language, we create space for genuine communication, trust, and respect. Instead of narratives that condemn, we craft stories that reflect reality—nuanced, complex, and always open to revision. The DMN doesn’t have to be the courtroom; it can be the library—a place of evolving understanding, not final verdicts.

Relationships thrive not when conflict is absent, but when we manage it thoughtfully. Being aware of the mind’s habit of narrative overgeneralization allows us to handle disagreements with grace, not aggression. Our brains might prefer simple stories, but our hearts and deepest connections need more courage. Marriage, family, and close friends need stories that are true enough to encompass all of us.

Narrative Over-generalization

10 Examples

Done Badly and Done Well

Overgeneralized (DMN default): “You always forget our anniversary.”

Reframed (reality-based): “When the date slipped your mind today, I felt sad. Part of me started spinning a story that maybe it doesn’t matter to you, but I know it probably does.”

2. Overgeneralized: “You never help with the kids.”

Reframed: “I felt alone tonight during bedtime. We’ve shared this before, so I’m wondering what got in the way for you this time.”

3. Overgeneralized: “You’re just like your father.”

Reframed: “When you shut down in conflict, it reminds me of patterns I’ve seen before—and it scares me. I don’t want to fall into the same old story.”

4. Overgeneralized: “You always make everything about you.”

Reframed: “Right now I’m feeling invisible in this conversation. My brain keeps saying, ‘See? It’s always like this,’but I know that’s not the whole truth. Can we make space for both of us?”

5. Overgeneralized: “You never listen.”

Reframed: “I didn’t feel heard just now. I noticed my mind instantly went to ‘you never care,’ but I’m trying to catch that story. I just need to feel understood in this moment.”

6. Overgeneralized: “You’re always negative.”

Reframed: “Lately, our conversations have leaned toward criticism, affecting how close I feel. I don’t want to fall into the habit of assuming the worst in each other.”

7. Overgeneralized: “You never show up for me.”

Reframed: “I really needed you this week and felt alone. Part of me jumped to ‘you never show up’—I want to name that, not accuse you, but so we can reconnect.”

8. Overgeneralized: “You always twist my words.”

Reframed: “I felt misunderstood in what I just said. My system went straight to ‘you’re twisting this on purpose’—but I want to believe you’re trying. Can we slow down and check it together?”

9. Overgeneralized: “You never change.”

Reframed: “I’m feeling stuck and discouraged, and my brain wants to fall back into ‘this is hopeless.’ But I know we’ve both made efforts. Can we look at where we’re still struggling?”

10. Overgeneralized: “You always make me feel small.”

Reframed: “In that moment, I felt diminished. I know that’s a tender spot for me, and my mind jumped to ‘you always do this.’ I want to stay in the moment, not the old wound.”

Digging Deeper:

1. On Forgetfulness

Done Badly: "You always forget what matters to me."

Done Well: "Today, you forgot our plans, which hurt my feelings."

2. About Listening

Done Badly: "You never listen!"

Done Well: "I noticed you seem distracted right now—can we talk later?"

3. Expressing Appreciation

Done Badly: "You never appreciate anything I do."

Done Well: "I would feel valued if you acknowledged my effort on this."

4. Dealing With Mistakes

Done Badly: "You always mess things up."

Done Well: "This mistake frustrates me, but let’s see how we can fix it together."

5. Regarding Time Management

Done Badly: "You’re always late and never respect my time."

Done Well: "It’s important to me that we start on time—how can we help each other with punctuality?"

6. Financial Conversations

Done Badly: "You always overspend and never think about our future."

Done Well: "Let’s talk about our spending priorities so we can plan our finances better."

7. Sharing Responsibilities

Done Badly: "I always have to do everything around here!"

Done Well: "I’m feeling overwhelmed right now. Could you help me with these tasks?"

8. Intimacy and Connection

Done Badly: "You never show affection anymore."

Done Well: "I miss our affectionate moments—can we find ways to reconnect?"

9. Parenting Differences

Done Badly: "You never support my decisions with the kids."

Done Well: "I felt unsupported earlier—can we discuss how we handle discipline?"

10. Communication Style

Done Badly: "You always make everything about yourself."

Done Well: "I’d like to share my feelings too; could you help me feel heard?"

Glossary of Terms

Narrative Over-generalization: A thinking pattern in which specific incidents are unfairly generalized into broad judgments using words like "always" and "never." This habit often creates misunderstandings and conflicts in relationships.

Predictive Reasoning: The brain anticipates events based on past experiences. It can make us mistakenly assume we know what someone else will say or do, affecting how we interpret interactions.

The Default Mode Network (DMN) is a network of brain areas that creates our internal story or sense of self. It shapes how we interpret experiences, often simplifying complex events into predictable (sometimes inaccurate) narratives.

Reality-Testing: A practice of gently checking the accuracy of our assumptions or generalizations in relationships. It helps reduce conflicts by clarifying misunderstandings.

Reframing is the skill of changing how we describe or interpret an event or behavior. It helps move conversations from negative generalizations to specific, solvable problems.

Defensiveness is an emotional reaction to feeling attacked or unfairly judged. Defensiveness often happens when broad negative statements like "always" or "never" are used.

Relational Harmony: A state of peace and mutual understanding in relationships, achieved by communicating specifically and compassionately rather than through generalizations.

Empathy is understanding and emotionally connecting with another person's perspective or feelings. It helps interrupt hostile generalizations by promoting understanding.

Conflict intensity is the strength or emotional charge of disagreements. Reducing over-generalizations can significantly lower conflict intensity, making arguments more manageable and productive.

Nuanced communication is a precise language rather than sweeping, generalized statements. It helps couples address the real issue clearly and constructively.

Predictive Reasoning: How the Stories in Your Mind Shape Your Marriage For Better And Worse

I Know What You Are Thinking!

Predictive Reasoning

How the Stories in Your Mind Shape Your Marriage For Better And Worse

By Don Elium, MFT

Every marriage is a story—but not just the one you consciously share with your spouse. There’s another story, silently running in the background, shaped by what neuroscientists call predictive reasoning. This invisible script influences how you interpret your partner’s tone, facial expressions, and intentions, often before they've even finished speaking. Without awareness, predictive reasoning can subtly erode trust and intimacy.

Predictive reasoning is your brain’s way of anticipating what comes next based on past experiences. Your mind doesn’t like surprises, uncertainty, especially emotionally charged ones, so it quickly fills in the blanks based on what’s happened before. For example, if your partner has previously been impatient when stressed, your brain instantly assumes they’re annoyed every time their voice takes on a sharper tone. This sets the stage for misunderstanding.

However, on the other hand, our brains are magnificent predictive machines, expertly crafted by evolution to help us survive by anticipating what’s coming next. This predictive reasoning allows us to conserve precious mental energy, avoid uncertainty, and react swiftly in critical situations. But what happens when the same predictive power that keeps us alive and efficient starts causing trouble in our closest relationships?

First, Our Predictive Reasoning is Your Brain’s Best Friend

Evolution gifted humans with predictive reasoning primarily for survival. Anticipating threats helped our ancestors quickly recognize and respond to danger. Neurologically, our brains learn to make predictions based on past experiences, saving us the energy to assess each new situation from scratch. Instead of processing every detail freshly, our brain takes shortcuts, using past experiences to predict what’s likely to happen next.

This energy efficiency is crucial. Our brains favor familiar scenarios because they require less cognitive effort. Predicting outcomes reduces uncertainty, which the brain experiences as stressful or threatening. Consequently, our brains developed intricate neurological systems—particularly the Default Mode Network (DMN)—to run these automatic predictions, enhancing our sense of safety and preparedness.

Secondly, Predictive Reasoning Can Become Your Relationship’s Worst Enemy

Predictive reasoning, while a powerful survival tool, can complicate relationships. Our brains don’t discriminate between anticipating external threats and predicting interpersonal interactions. We start creating “mental movies” based on past interactions, assuming we know precisely how friends, family members, or partners will react, often inaccurately.

This misapplication leads to repeated conflicts, misunderstandings, and emotional distance as relationships become victims of predictive errors. Recognizing these tendencies is the first step toward healthier interactions.

Consider this scenario: Jane notices Mark seems quiet after coming home from work. Her predictive reasoning kicks in immediately: "He must be upset with me again," even though Mark is tired from a long day. Jane’s assumption triggers defensiveness, leading to tension where none actually existed. The trouble is, Jane’s brain truly believes its interpretation. To her, Mark’s silence means rejection.

Predictive reasoning is particularly influential during conflicts. When emotions run high, we rely heavily on past patterns to interpret the present. A simple disagreement about chores can rapidly escalate because each partner is convinced they already know what the other will say or do. The brain defends these assumptions fiercely, making open-minded conversation difficult.

But predictive reasoning is not all bad. It’s an evolutionary gift, designed to keep us safe by preparing for danger or disappointment. The problem arises when our brain applies these survival instincts to everyday relational interactions. Rather than keeping us safe, these automatic assumptions may close down dialogue, intimacy, and growth.

The first step in managing predictive reasoning positively is becoming aware that your brain naturally jumps to conclusions. Pausing to ask yourself, "Am I reacting to what's really happening, or to my assumptions?" can significantly shift how you approach interactions. For instance, Jane might gently say, “Mark, I notice you’re quiet—is everything okay?” instead of immediately assuming he's upset with her.

The next step involves what relationship researchers call "reality-testing." Instead of acting on assumptions, gently verify them with your partner. Reality-testing might look like this: "When you answered quickly just now, my mind went straight to feeling criticized. Is that what you meant?" This practice provides the brain with new, accurate data and helps rewire predictive patterns.

Additionally, fostering empathy actively disrupts negative predictive loops. Empathy means consciously stepping into your partner’s perspective. Mark, sensing Jane’s unease, might respond empathetically: "I realize I'm quiet. I’m actually just exhausted. I’m not upset with you." Such clarifications not only clear up misunderstandings but also build trust.

Couples who thrive practice these techniques regularly, turning predictive reasoning from a source of conflict into a bridge for deeper understanding. They begin treating their assumptions as hypotheses to be gently tested, rather than certainties to defend. Over time, this shared curiosity becomes part of their relational culture.

Ultimately, predictive reasoning reveals something profound: the health of your marriage depends as much on the stories you tell yourself as the interactions you have together. Learning to recognize, question, and update these internal stories can transform your marriage from a cycle of automatic reactions to a deliberate and mindful partnership—one in which both partners feel truly seen and understood.

Glossary of Terms

Predictive Reasoning

The brain’s natural process of anticipating what will happen next based on past experiences and memories. It helps us navigate the world but can lead to misunderstandings in relationships when assumptions are incorrect.

Reality-Testing

A technique of checking assumptions or interpretations by calmly asking your partner if your perception matches their intent. It helps reduce misunderstandings and conflicts.

Empathy

The ability to understand and share the feelings or perspective of another person. Empathy helps disrupt negative assumptions by allowing you to understand your partner’s actual emotional state.

Survival Instincts

Automatic protective responses of the brain designed to anticipate threats. When misapplied in relationships, these instincts can cause unnecessary defensiveness and conflict.

Relational Culture

The shared norms, habits, and values within a relationship. When couples practice empathy and open communication regularly, they build a healthy relational culture.

Hypotheses vs. Certainties

Treating your assumptions as possibilities to explore (hypotheses), rather than absolute truths (certainties). This mindset allows openness and dialogue instead of defensiveness.

——-

Here are 10 common relationship scenarios illustrating predictive reasoning done badly, each immediately followed by an improved version of how it can be done well:

1. Coming Home Quietly

Done Badly:

Jane assumes: "He's quiet again—he's annoyed at me." She withdraws silently, hurt and defensive.Done Well:

Jane says: "I notice you're quiet. Are you okay, or just tired?"

2. Late Response to Text

Done Badly:

Mark thinks: "She hasn't replied; she must be ignoring me intentionally." He sends a passive-aggressive follow-up message.Done Well:

Mark thinks: "Maybe she's busy." He texts gently, "Hope everything's okay—let me know when you're free."

3. Short Answer During a Conversation

Done Badly:

Anna thinks: "He must not care about my feelings." She responds with irritation, escalating into an argument.Done Well:

Anna checks in: "You seem distracted; is this a good time to talk?"

4. Household Chores

Done Badly:

Tim assumes: "She's not helping because she expects me to do everything." He becomes resentful without asking for help.Done Well:

Tim asks calmly: "Can we discuss chores? I'm feeling overwhelmed and could use some help."

5. Misunderstood Comment

Done Badly:

Sara thinks: "That joke was meant to embarrass me." She withdraws, silently upset.Done Well:

Sara clarifies gently: "That comment hit me wrong—did you mean it the way I heard it?"

6. Making Plans

Done Badly:

David thinks: "She never considers my schedule." He becomes defensive and cancels plans without explanation.Done Well:

David expresses openly: "I'd love to make that work, but can we check the schedule first?"

7. Expressions and Tone

Done Badly:

Ella assumes: "He rolled his eyes—he thinks I’m ridiculous." She immediately snaps back defensively.Done Well:

Ella pauses and asks calmly: "You seem frustrated. What's going on?"

8. Money Conversation

Done Badly:

Mike predicts: "She always judges my spending." He hides expenses, causing mistrust.Done Well:

Mike approaches openly: "I want to share my thoughts on spending; can we talk comfortably about this?"

9. Initiating Affection

Done Badly:

Rachel thinks: "He didn’t hug me—he’s pulling away." She becomes distant without explanation.Done Well:

Rachel expresses gently: "I'd love a hug—are you okay?"

10. Disagreement Over Parenting

Done Badly:

Paul thinks: "She always undermines my decisions." He responds aggressively, escalating conflict.Done Well:

Paul reflects and says: "I feel we’re seeing this differently. Can we discuss our parenting approaches?"

——

Reflective Prompts

Awareness Check-In

Reflect on a recent misunderstanding with your partner. Write down what your predictive reasoning initially assumed. Was it accurate?Reality-Testing Practice

Identify one common assumption you frequently make about your partner. How might you gently check its accuracy next time?Empathy Exercise

Recall a recent moment when you felt misunderstood. What might your partner have been feeling or thinking at that time?Hypothesis Exploration

What story about your relationship do you tend to treat as a certainty? What changes if you begin treating it as a hypothesis instead?Cultivating Curiosity

How can you encourage more curiosity in your relationship? Write two questions you can regularly ask each other to foster openness and understanding.

Why Your Brain’s Story Isn’t Always True

Part 1

Why Your Brain’s Story

It isn’t Always True

The Default Mode (Self-Identity) Network

By Don Elium, MFT

The human brain is a storyteller, constantly working to make sense of our experiences. At the center of this storytelling system is the Default Mode Network (DMN)—a group of brain regions that light up when we’re not focused on an external task. It activates when we daydream, reflect, plan, remember the past, or imagine the future. In short, the DMN is where our sense of self lives. It helps us answer the question: “Who am I?”

But here’s the twist. The DMN doesn’t prioritize truth—it prioritizes stability. Its job is not to give us a clear picture of reality, but to keep our identity and worldview consistent enough that we feel safe and predictable to ourselves. If something threatens that sense of inner stability, the DMN is more likely to distort, deny, or reframe the story rather than rewrite it completely. The result? We often tell ourselves narratives that feel true, but aren't necessarily rooted in objective reality.

This is especially true in moments of stress or emotional vulnerability. When hurt, shamed, or afraid, the DMN quickly creates a storyline to protect us from feeling unstable. For example, if we were ignored as children, the DMN might form the belief: “I must not matter.” Once repeated and emotionally reinforced, this belief gets wired in—not because it’s true, but because it helps the brain make sense of emotional pain. It becomes part of our default identity.

The DMN is a survival tool. It helps us filter overwhelming input, store emotional memories, and create meaning in chaos. But this comes at a cost. If left unexamined, the DMN will keep repeating old stories—even painful or limiting ones—because they feel familiar. Familiarity is safety to the DMN, even if the narrative is no longer helpful or accurate. Many people find themselves stuck in patterns they can’t explain: their brain runs on an outdated self-story.

One of the most fascinating things about the DMN is that it’s not fixed. It can be updated—but only under certain conditions. During periods of neuroplasticity (such as therapy, grief, meditation, or psychedelic experiences), the DMN becomes more flexible. New experiences contradicting the old story—if they’re emotionally powerful and repeated—can rewire the network. This is how people change how they act and who they believe themselves to be.

Another key feature of the DMN is that it works in loops. Once it settles on a narrative, it will seek evidence to support it. This is known as confirmation bias. If your DMN carries the belief “I’m not good enough,” it will subtly filter your memories and daily experiences to reinforce that story. You may not notice the compliments, but you’ll remember the criticisms. Not because you’re weak, but because your DMN is trying to stabilize your identity by staying consistent.

What’s more, the DMN doesn’t always work alone. It interacts with emotional centers like the amygdala and hippocampus, which help tag memories with feelings. That’s why emotional memories feel more real than factual ones. If something felt intense, especially during childhood or trauma, it often gets locked into the DMN as a core part of identity. Over time, we stop questioning it. We say, “That’s just who I am,” when it may be a survival story the brain chose, not a truth we consciously created.

This is why therapeutic work often focuses on gently confronting the old stories we carry. The goal isn’t to shame the DMN, but to update it—to offer new, emotionally grounded experiences that reshape the story it tells. When we feel safe enough to be seen, challenged, and supported, the brain can rewrite the loops it once clung to. This is identity work. And it’s what makes real healing possible.

So the next time you hear a harsh or limiting voice in your head, pause. Ask yourself: “Is this true, or just familiar?” That question alone can create a crack in the DMN’s certainty, and a new story can grow in that crack. One that’s more honest, compassionate, and aligned with who you are becoming, not just who you’ve been.

In the end, the DMN is not the enemy. It’s the keeper of continuity, the architect of the self. But without awareness, it can become a prison of old beliefs. With awareness, safety, and repeated experience, it becomes a living story that can evolve as you do.

Part 2

The Awareness Network

The Brain's Key to

Seeing Clearly What Is True

By Don Elium, MFT

Most assume that being aware means simply noticing what’s around us. However, in neuroscience, awareness is a specific, measurable brain function. It has its network, separate from the one that handles our self-story. This Awareness Network plays a crucial role in helping us perceive reality in real time, without the filters, assumptions, or biases created by our personal history. Understanding this network is essential for anyone interested in mindfulness, healing, or genuine transformation.

The brain operates through networks—clusters of regions that light up together and work as a system. Two of the most important are the Self-Identity Network (often called the Default Mode Network, or DMN) and the Awareness Network, sometimes referred to in neuroscience as the Task-Positive Network or the Salience/Executive Control Network. These networks operate in a rhythm, often switching control back and forth depending on what’s happening.

The Self-Identity Network is where our personal story lives. It reflects on the past, imagines the future, tracks our place in social relationships, and creates a sense of "me." This network is active when we’re daydreaming, remembering, or ruminating. It helps us maintain continuity, meaning, and a coherent narrative about who we are. But it isn’t always grounded in the present. Its priority is to keep us emotionally and psychologically stable—even if that means distorting reality.

By contrast, the Awareness Network is the system that brings us into the here and now. It engages when we are entirely focused on what is happening in the moment, during meditation, deep listening, sensory awareness, or when we’re present in our bodies. This network allows us to observe thoughts, emotions, and sensations without immediately identifying with them. Mindfulness traditions often describe the “witnessing self” as consciousness without attachment.

Where the DMN tries to make meaning, the Awareness Network takes things in. It notices without needing to interpret. It allows us to track what is actually happening, not just what we expect or fear. This is why mindfulness and meditation practices are so powerful. They increase activation of the Awareness Network while reducing activity in the DMN, allowing us to step outside the loops of old self-narratives momentarily.

But the goal isn’t to shut down one network and favor the other. The healthiest forms of self-awareness arise when the two networks work together. When the Awareness Network is strong, it can observe the activity of the Self-Identity Network with curiosity and perspective. It allows us to say, “Oh, I’m thinking that old thought again,” instead of unconsciously living inside it. This interface is the birthplace of choice and real inner growth.

In neuroscience terms, this means building a bridge between narrative and presence. That bridge is where actual self-awareness lives. Without it, we’re either lost in our stories (over-identified with the DMN) or detached from meaning (over-identified with pure observation). But when both are online, we can observe our patterns, question our beliefs, and maintain a grounded sense of self.

Practices like mindfulness, somatic therapy, and breathwork strengthen the Awareness Network. Over time, this leads to less emotional reactivity and a more flexible identity. When you’re aware that your mind is pulling you into an old survival loop, you have a moment of space. And in that space, you can choose a new response.

This is the foundation of emotional regulation, personal growth, and healing from trauma. The Awareness Network allows us to feel a feeling without becoming the feeling. It lets us name an old belief without being consumed by it. And most importantly, it gives us access to the part of ourselves that can change the story, not just survive inside it.

So if you’re on a path of transformation, don’t just ask, “Who am I?” Ask also, “Who is noticing?” The Self-Identity Network will answer with history and habit. But the Awareness Network will pause and say, “This is what’s here now.” And from that place, something new can begin.

———-

Glossary of Terms

Awareness Network

A brain system that helps us stay fully present in the moment. It allows us to notice thoughts, emotions, and sensations without becoming overwhelmed or reactive. Also called the Task-Positive Network or Executive Control Network.

Self-Identity Network

The brain network stores our personal story, memories, and beliefs about who we are. Known in neuroscience as the Default Mode Network (DMN), it creates a continuous sense of self, but can also distort reality to keep us feeling emotionally stable.

Default Mode Network (DMN)

A network in the brain that activates when we’re not focused on the outside world. It helps us think about ourselves, reflect on the past, plan for the future, and make sense of our lives—but it often runs on old habits and assumptions.

Task-Positive Network

Another name for the Awareness Network. It becomes active when we focus on a task, pay close attention, or stay mindful in the present moment.

Salience Network / Executive Control Network

Neuroscience describes parts of the awareness network that help us filter what matters, shift attention, and stay focused on what’s real or necessary.

Narrative Self

The inner story we tell ourselves about who we are is shaped by our past experiences, emotional memories, and repeated thoughts. This narrative lives in the DMN and often goes unchallenged unless observed by the Awareness Network.

Witnessing Self

The part of our mind that can observe without reacting. It notices what’s happening inside us (thoughts, feelings, body sensations) with curiosity rather than judgment. Often accessed through mindfulness and meditation.

Self-Awareness

Self-awareness is the ability to recognize our thoughts, feelings, and behaviors in the moment. Accurate self-awareness happens when the Awareness and Self-Identity Networks work together—when we can observe our patterns without getting lost.

Over-Identification

When we become so fused with a thought, belief, or emotion, we mistake it for who we are. This often happens when the DMN dominates and the Awareness Network is underused.

Mindfulness

A practice that trains the brain to stay focused on the present moment with openness and acceptance. It strengthens the Awareness Network and helps us respond to life more clearly than habitually.

Emotional Reactivity

Acting out of intense emotion without space to think clearly. Strengthening the Awareness Network can reduce reactivity by helping us pause and choose our response.

Somatic Therapy

A therapeutic approach that focuses on body awareness to heal emotional wounds. By staying present with bodily sensations, we activate the Awareness Network and bring safety into the nervous system.

Awareness Network

A brain system that helps us stay present in the moment. It allows us to observe thoughts, feelings, and sensations without getting caught in them. Also known as the Task-Positive Network or part of the Executive Control Network.

The Self-Identity Network

The Default Mode Network (DMN) creates our internal story—how we see ourselves, remember the past, and imagine the future. It’s responsible for our sense of self, but can repeat old beliefs and distort reality for emotional stability.

The Default Mode Network (DMN)

is an active network in the brain when we’re thinking about ourselves, daydreaming, or reflecting. It helps maintain a sense of “me” across time, but often relies on familiar patterns rather than accurate or present-based thinking.

Emotional Regulation

The ability to stay steady and grounded when emotions arise. It improves as the Awareness Network strengthens, allowing us to respond instead of react.

Narrative Identity

The DMN is the story we tell ourselves about who we are. Built from memories, beliefs, and past experiences, it shapes and influences how we react and relate to others.

Mindfulness

The practice of paying attention to the present moment without judgment. It strengthens the Awareness Network and helps us observe our thoughts rather than be controlled by them.

Over-Identification

When we get caught in a thought, feeling, or belief and mistake it for who we are. This often happens when the DMN is dominant and the Awareness Network is underactive.

Self-Awareness

The ability to notice and reflect on our thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. Accurate self-awareness arises when the Self-Identity Network and the Awareness Network work together.

Task-Positive Network

A term often used for the Awareness Network. It turns on when we’re focused on a task or in the present moment. It helps us observe without attaching to stories or interpretations.

Witnessing Self

A term often used in mindfulness traditions describes the part of us that can observe without reacting. It lives in the Awareness Network and helps us track what’s happening without immediately identifying it

Relational Identity and Forever Bonds

Your Relationship Has A Shared Neurological Network

Relational Identity and Forever Bonds

By Don Elium, MFT

Relational identity—who we believe to be about others—is one of the most enduring and neurologically influential aspects of the self. Far from being a fixed trait, our relational identity is formed and reformed through a continuous interplay of memory, emotion, social feedback, and neuroplastic development. At the core of this system lies the brain’s deep desire for safe connection, and when that connection is felt in a profound or transformative way, it can leave a lasting imprint: what some might call a forever bond.

These bonds are emotional and neurobiological structures built through repetition, intensity, and co-regulation. When two people engage in sustained, emotionally attuned experiences—whether through love, friendship, caregiving, or even shared adversity—their brains begin to co-wire. The default mode network (DMN), which houses our identity and self-story, integrates “the other” as part of that story. In other words, we don’t just remember someone; we neurologically internalize them.

One of the brain systems most involved in creating these enduring attachments is the limbic system, particularly the amygdala (which tags emotional significance) and the hippocampus (which encodes memory). When emotionally significant experiences are repeated in a safe, attuned way—especially during times of vulnerability—the brain creates emotionally tagged memory clusters. These memories become what happened and who we are with that person. That’s relational identity.

Another key player in forming forever bonds is oxytocin, often called the “bonding hormone.” Released during physical affection, eye contact, shared joy, and especially during states of emotional safety, oxytocin strengthens trust and emotional recall. More importantly, it reinforces neural associations between the other person and a sense of calm or belonging. This means the person becomes psychologically important and neurologically associated with regulation, relief, or aliveness.

Relational identity also encompasses mirror neuron systems, which assist us in internalizing the emotional states, expressions, and even thought patterns of those we’re close to. These neurons, activated when we observe another person, help explain why we often finish each other’s sentences, mimic gestures, or feel “off” when they are distressed. Over time, repeated exposure to each other's emotional cues alters our brain circuitry, making the relationship a part of our emotional homeostasis.

Forever bonds frequently form during states of heightened neuroplasticity: childhood, early romantic love, periods of crisis, or altered states (including grief, trauma, or psychedelics). The brain is more receptive to encoding new relational data in these contexts. If the experience is positive and deeply felt, the other person's neural signature becomes enduring, even if the relationship ends, changes, or becomes distant.

In therapeutic or integration work, we often see that relational ruptures—breaks in trust, loss, abandonment—impact the brain not only emotionally but also structurally. The loss of a forever bond can feel like losing part of oneself, because that’s exactly what’s happening from a neurological standpoint. The part of the brain that codes “I am safe with you” or “I feel known here” goes offline, and the identity formed in that space may temporarily collapse.

However, the exact neuroplastic mechanisms that create forever bonds can be re-engaged for healing. When new relational experiences provide emotional attunement, co-regulation, and safety, primarily through repetitive, embodied interactions, the brain can remap connections and reassign safety. This doesn’t erase the forever bond but creates a more nuanced relational identity that holds loss and renewal simultaneously.

What’s most important to understand is that relational identity is not simply a mental construct but an embodied neurological state. Who we are in connection is wired into our brains. When that connection is consistent, emotionally rich, and co-regulated, it leaves a lasting imprint. Forever bonds are not a poetic idea; they are a biological truth.

And yet, as neuroscience now shows, forever bonds do not equate to a frozen identity. Even in adulthood, the brain can re-open to love, trust, and safety when the conditions are present. The stories we carry in our DMN about our identities about others, and theirs about us, can be updated—not by logic alone, but through new experiences of being seen, held, and known. Ultimately, relational identity is not only what shaped us—it is also what can heal us.

Glossary of Terms

Here is a Glossary of Terms written for a general audience, based on the article The Neurology of Relational Identity and Forever Bonds by Don Elium, MFT:

Relational Identity

The sense of who we are in connection with others. It’s shaped by how we’re treated and feel when we’re with someone, and the emotional roles we’ve repeated in relationships over time.

Forever Bonds

Deep, long-lasting emotional and neurological connections formed with people who made us feel safe, seen, or profoundly affected. These bonds are stored in the brain and can last even if the relationship changes or ends.

Neuroplasticity

The brain can change its structure and function in response to experience. It’s how we grow, heal, and form new patterns—even into adulthood.

Co-Wiring

Two people’s brains begin to sync through repeated emotional connection, such as eye contact, shared experiences, or deep conversations. Over time, their nervous systems influence each other.

The Default Mode Network (DMN)

A part of the brain involved in self-reflection, memory, and storytelling. It helps form our identity and personal history. The DMN integrates important people into our self-narrative over time.

Limbic System

The brain’s emotional processing center. It includes structures like the amygdala and hippocampus that help us respond to emotional events and store emotional memories.

Amygdala

A small, almond-shaped part of the brain that helps detect and tag emotional significance, especially in moments of fear, excitement, or attachment—the Threat Detector.

Hippocampus

The part of the brain involved in forming new memories. It helps encode the emotional and relational context of experiences, especially those that repeat or feel meaningful.

Emotionally Tagged Memory Clusters

Groups of memories that are emotionally charged and stored together. These clusters help shape how we feel about ourselves and others in relationships.

Oxytocin

A hormone often called the “bonding hormone.” It’s released during touch, trust-building moments, and emotional closeness. It helps the brain make a connection with safety and belonging.

Regulation (Emotional Regulation)

The ability of the nervous system to stay balanced and calm. In close relationships, we often help each other regulate through voice, touch, and presence—co-regulation.

Mirror Neurons

Brain cells that help us understand and feel what others are experiencing. When someone smiles or cries, our mirror neurons respond like we think the same, helping us connect emotionally.

Emotional Homeostasis

A state of emotional balance. In relationships, we can develop emotional rhythms with others that help us feel steady. Losing those rhythms, such as after a breakup, can disrupt our internal balance.

Relational Rupture

A break in trust or connection within a relationship, such as through abandonment, betrayal, or emotional withdrawal. Ruptures can affect both our emotional and neurological sense of identity.

Integration Work

The therapeutic or intentional process of making sense of emotional experiences, especially those involving strong connections or trauma, so that the nervous system can heal and form new, healthier patterns.

Re-Mapping Connection

A healing process where the brain forms new associations with safety, trust, or emotional closeness. This allows us to create new secure relationships, even after painful ones.

Embodied State

A way of experiencing self or identity that is not just a thought, but something felt physically in the body. In relational identity, we feel who we are in someone’s presence—calm, anxious, firm, or small.

Repetitive, Embodied Interactions

Regular, emotionally safe moments of connection (like eye contact, consistent care, or shared silence) that help rewire the brain’s expectations of what connection feels like.

Narrative Repair

The process of updating the story we tell about ourselves in relationships, often by experiencing new, healthier forms of connection that contradict old beliefs rooted in hurt or trauma.

Healing Through Relationship

Just as relationships can hurt us, they can heal us by offering emotional safety, consistency, and acceptance. This kind of healing is both emotional and neurological.

How Your Nervous System Decides Who Feels Safe: Neuroception

Neuroception: How Your Nervous System Decides Who Feels Safe

By Don Elium, MFT

Every romantic, familial, or professional relationship has a silent, split-second process beneath the surface. Your nervous system asks before you speak and think: Am I safe with this person? That subconscious evaluation is called neuroception—a term coined by Dr. Stephen Porges, the developer of Polyvagal Theory. Neuroception is how our bodies detect safety or threat in others without conscious awareness.

Unlike perception, which uses our five senses and logic, neuroception operates automatically. It doesn’t ask what’s true; it asks what’s familiar or emotionally coded as safe or dangerous. This means our reactions to people often have less to do with what they’re saying and more with how our nervous system unconsciously interprets their tone, posture, facial expression, or presence.

Neuroception plays a significant role in responding to relationships' intimacy, conflict, or vulnerability. If someone’s body language reminds us—even vaguely—of an experience of danger or emotional pain, our nervous system may register them as unsafe. This can happen even when the person is entirely trustworthy. We may feel shutting down, pulling away, or becoming defensive without knowing why.

Neuroception is why “overreactions” in relationships often aren’t overreactions. They’re under-recognized survival patterns. If your partner’s raised voice or sudden silence activates a memory of rejection, your body may shift into fight, flight, or freeze. You’re not overthinking—you’re under-protecting. Your system is reacting faster than your thoughts can catch up.

This becomes especially important in long-term relationships, where repeated misreads between partners can lead to chronic misunderstanding. One person might withdraw, triggering abandonment in the other. That person then pursues, which is read as pressure, and the cycle continues. Without recognizing neuroception, couples often blame each other for patterns rooted in unspoken nervous system cues.

The good news is that neuroception can change. Through co-regulation—the process of calming each other through tone, breath, eye contact, and steady presence—we can begin to teach our nervous systems that connection is safe. This is why repair after conflict is so powerful: it doesn’t just solve the problem, it rewires the relational code between two people.

One key to changing neuroception is consistency. Occasional warmth or apology may not be enough to update old wiring. The nervous system needs repeated signals of safety—softened tone, open body language, non-defensive listening—to form new default settings. Over time, the presence that once felt threatening begins to register as trustworthy.

Therapy, mindfulness, and somatic work can help individuals become more aware of their neuroceptive patterns. By tracking body sensations, breath changes, and emotional shifts in real time, we start to notice: I’m reacting to a feeling, not necessarily to this person. This awareness creates the space to pause, regulate, and respond differently.

Ultimately, neuroception reminds us that relationships are not just intellectual agreements or emotional bonds—they are nervous system exchanges. Our bodies are speaking to each other even when words fail. Talking about safety language—through presence, tone, rhythm, and consistency—builds absolute trust.

So, if you’ve ever wondered why you overreact, shut down, or feel uneasy with someone for “no good reason,” remember: your nervous system is trying to protect you. But with patience, awareness, and a safe connection, you can update the code. In doing so, you can reshape how you relate to others and how your body experiences love, safety, and belonging.

————————

Glossary of Terms

Neuroception

An automatic process where the nervous system senses whether a person or situation feels safe, dangerous, or life-threatening, without conscious thought. Coined by Dr. Stephen Porges, neuroception happens faster than thinking and is often based on body language, tone, and emotional cues.

Perception

The process of consciously noticing and interpreting the world through the five senses and reasoning. Unlike neuroception, perception is slow, deliberate, and influenced by thought.

Polyvagal Theory

A scientific framework developed by Dr. Stephen Porges that explains how the vagus nerve influences our emotional and physiological responses, especially how we connect, disconnect, or defend ourselves in social situations.

Fight, Flight, Freeze

Automatic survival responses triggered when the nervous system detects danger.

Fight = anger, argument, or defensiveness

Flight = withdrawal, avoidance, or escape

Freeze = shutting down, going numb, or feeling stuck

Fawn = appeasing while masking how you really feel

Co-Regulation

The calming process happens when two people help regulate each other’s nervous systems through safe, steady cues, like tone of voice, eye contact, or physical presence.

Somatic Awareness

The ability to notice and interpret body sensations (tightness, breath, heart rate) as indicators of emotional or nervous system states. Somatic awareness helps identify neuroceptive triggers in real time.

Emotional Memory

A stored experience that includes feelings, body reactions, and meaning. These memories can influence how our nervous system responds to people or situations, often without us realizing it.

Relational Repair

The process of restoring safety and trust in a relationship after a rupture, misunderstanding, or conflict. It helps update the nervous system’s sense of whether the connection is safe again.

Triggered

A strong emotional reaction (often fear, shame, or anger) caused by something that reminds the nervous system of a past pain or threat, even if it’s not dangerous now.

Survival Pattern

An ingrained emotional or behavioral response—like shutting down or lashing out—that was originally formed to protect us in unsafe environments. These patterns often get activated by neuroception, even in safe relationships.

Safety Cues

Signals that tell the nervous system it's okay to relax. These include soft facial expressions, gentle tone of voice, relaxed posture, and consistent, non-threatening behavior.

The Gentle Art of Asking: Favors, Flaws, and the Marriage That Breathes

The Gentle Art of Asking: Favors, Flaws, and the Marriage That Breathes

By Don Elium, MFT:

“He knows I hate it when he leaves dishes in the sink.” “She never puts the keys back in the same place.” “We’ve been over this. A hundred times.”

There comes a point in every marriage where patterns feel carved in stone—those little habits that don’t quite disappear, even after therapy, agreements, and a dozen hopeful recommitments. You want something to change or be easier, and you’ve tried. They’ve tried. But life happens. Energy runs thin. And you find yourself standing at the edge of the same old sink.

So what then? Give up? Blow up? Keep score?

Actually—ask.

Not demand. Not guilt. Please don’t rehearse your closing argument from the bench of righteous frustration.

Could you ask for a favor?

Favors, Not Fixes

In the Gottman framework, we often say that 69% of marital conflict is perpetual. That means it’s not going away. These differences in personality, upbringing, temperament, or neurology don’t get “solved”—they get navigated. And here’s where the art of asking comes in.

A favor isn’t a fix. It’s a request for support that acknowledges both of your limitations.

When one partner says, “Can you try to remember to lock the side door at night? I know it’s not easy for you to remember, but it helps me sleep,” they are inviting care. They are not pretending it’ll become a flawless habit. They ask for love to override wiring and grace to float into imperfection.

Favors work where ultimatums fail because they make room for the truth:

Some habits will never be fully broken. Some needs will never be fully met. But love can stretch.

When You Ask for a Favor, You Say:

“I know you, and I’m not here to change you.”

“This matters to me, even though it might be small.”

“You matter enough to me to ask kindly.”

“We’re on the same team.”

And on the flip side, when you do the favor, even if you forget the next night, you’re not just helping with the keys, dishes, or lights. You’re participating in emotional generosity, a key trait in high-functioning couples

How to Ask in Gottman Style:

Soften the Startup.

Instead of: “Why do you always leave the side door unlocked?”

Try: “Hey love, I know the side door’s tricky to remember sometimes… would you mind helping me feel safer by double-checking it before bed?”

Accept Influence.

If your partner responds, “Sure, and maybe you could help me remember in case I forget?” — say yes. Marriage thrives when partners let each other’s needs shape their behavior.

Honor the Effort, Not Just the Outcome.

• Did they remember three nights in a row? Celebrate that.

• Did they forget the fourth? Don’t erase the first three. Reinforce progress, not perfection.

Make Peace with the Repeat.

Sometimes, you will need to ask again. This is not failure. It’s maintenance. A good marriage isn’t a contract you sign once—it’s a conversation you keep choosing to have.

Use Gentle Humor If That’s Your Language.

“I’ll trade you one locked side door for two lights off in the guest bathroom.”

A little levity can disarm defensiveness, but only if both people feel safe.

What If They Say No?

Then you listen. A favor is not owed. And sometimes your partner doesn’t have it in them that day. The key is to let the “no” be part of the relationship—not the end of the goodwill.

You can always revisit it later with curiosity: “Hey, I noticed you said no the other day. Is that something that feels hard for you right now?”

Final Thought

You don’t need a flawless partner. You need a willing one.

And they don’t need a flawless you. They need someone who can ask gently, not because they’re weak, but because they believe in a connection stronger than resentment.

The Gottmans call these moments “bids for connection.” A favor asked softly becomes a bid. And in healthy couples, these bids aren’t just received—they’re honored. Even when the sink still has dishes. Even when the side door gets missed.

Because the marriage that breathes is not the one that perfects—it’s the one that keeps reaching, gently, through the cracks.

"It Isn't Fair": They're asking you to listen differently

By Don Elium, MFT

When a spouse, a relative, a friend, or a family member says, "It isn't fair," most people hear a criticism. However, anyone who listens beneath the surface—understand it is much more than that. It serves as a flare, a signalng that someone is struggling to fully articulate something that is not quite there yet. Beneath that small phrase often lies a complex emotional truth: a mix of in the words to express something that needs more air, more words: grief, resentment, exhaustion, and longing.

In family systems, fairness is rarely distributed clearly. Roles develop early, often without consent.

Trying to maintain the peace, parents often feel overwhelmed. Marriages fray. Friendship circumstances change. The phrase "It isn't fair" can mark the moment a long-silent voice finally speaks up—and it rarely pertains to the issue being debated at the surface. It's about history. About emotional labor.

Could be a teenage son watching his older sister spiral out yet again. His parents, distracted by the crisis, overlook his quiet slipping away. When he says, "It's not fair that she always gets away with it," he's not just angry—he's lonely. He wonders what he has to do to matter just as much. Beneath that protest lies a plea: "Will anyone notice me if I don't fall apart?"

Even in seemingly minor disputes, the phrase "It isn't fair" can signal the return of a younger part of the self-identity that never got to protest back then and is finally speaking now. In those moments, we aren't merely witnessing someone express a current frustration; we're observing a flashback—an unresolved emotional truth that has found a crack in the conversation wide enough to escape in an effort to be heard, seen differently, and met with engagement of curiosty instead of defensiveness.

It opens a door; if we pause and lean in, we might ask, "What part of this feels especially unfair to you?" or "Is there more to this?" These questions invite emotional specificity; when that specificity arrives, what seemed like a complaint becomes more clear. The speaker may realize they're not just upset about this weekend or this fight; they're exhausted from a pattern that has never been named.

In families and close friendships, fairness often masquerades as equality. However, emotional fairness rarely means everyone gets the same; it means everyone is requesting to get what they need. When needs go unmet for too long, resentment starts to ferment. "It isn't fair" is often the first sign that someone's internal balance is trying to right itself through clarity. Maybe they've been giving more than they've been receiving and need to be witnessed before they can reset.

This phrase also signals risk. Saying "It isn't fair" out loud in a family system can feel dangerous; it disrupts the known script or a story that maybe once was true but is not longer. Leaning into “It isn’t fair” differently can expose a hidden ledger of emotional debts and asking others to confront something they may not be ready to face. It often gets shut down quickly—minimized, redirected, or turned into a debate. But if held gently, it can transform the conversation entirely toward clarity, relief, and letting go of some misunderstanding; a re-connection of the heart?

Ultimately, when someone says, "It isn't fair," they're not asking you to fix everything. They are asking you to listen differently, feel with them, and see something they've been holding alone. In that way, the phrase isn't just a complaint—it's a crack in the wall, an opening for truth, connection, and healing; not always comfortable, but always vital.

So the next time you hear those three words—"It isn't fair"—don't rush to explain or defend. Try to pause, reset, get curious, and ask what they've been carrying that deserves attention. “It isn’t fair” can become an opportunity for connection. It will be bumpy, but if you engage with the bumps with curiosity and compassion, you may hear the real story waiting to be told, and new doors can open.

“Out beyond ideas of wrongdoing and rightdoing, there is a field. I will met you there.” —-RUMI

“The past does not create the present, unless you insist.” —ALAN WATTS

A Whole Layer Of Grief: It Doesn’t Follow Rules

A Whole New Layer of Grief: It doesn’t follow rules

By Don Elium, MFT

Grief doesn’t adhere to any rules. It doesn’t follow a straight path or conform to neat stages. Sometimes, it arrives like a wave; other times, it hits you unexpectedly on a Tuesday while you're folding laundry. For many people, the most surprising aspect of grief is how it manifests in layers. You may think you’re mourning one thing—a death, a divorce, a farewell—but suddenly, you’re engulfed by sorrow you weren’t aware you still held. That’s not a failure; it’s layered grief.

Layered grief occurs when the pain of a current loss awakens past losses that were never fully addressed. You might lose a parent and suddenly feel the pang of losing a childhood friend who moved away when you were ten. You might experience a breakup and, oddly, find yourself weeping over your father, who never embraced you. It can feel disorienting, even unsettling—like grief is multiplying. However, what is happening in your nervous system is that old grief is finally coming to the surface because this new loss has opened something up.

This is more common than we admit. Most of us weren’t taught how to grieve. Instead, we were taught to suppress, move on, and hold it together. As a result, earlier griefs get stored—emotionally, physically, even neurologically. The body remembers, and the heart does too. Those older wounds don’t just stay quiet when we face new loss; they raise their hands and demand to be felt as well. That’s not regression—it’s healing, finally getting a turn.

Grief is often described in stages—denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. However, that model was never intended to serve as a roadmap. It was a set of potential landmarks. The true terrain of grief is far messier. It circles back, deepens, and can remain quiet for years only to return with force when something else triggers it. Layered grief occurs when life gives us another rupture—and we find we were already cracked.

This isn’t just emotional; there’s real brain science involved. When we grieve, our limbic system—the emotional processing center—activates old neural pathways associated with memory, safety, and attachment. If a previous loss was never fully processed, your brain connects the new loss to the old one. Suddenly, you’re grieving at a depth that feels disproportionate to the moment. However, it’s not disproportionate; it’s layered. Your nervous system is attempting to metabolize what it didn’t process before.

That’s why grief doesn’t always make sense to others. They see what you lost, but they don’t understand what that loss connects to. You do; you feel it. Sometimes, that may cause you to question your sanity or strength. Please don’t. There’s nothing wrong with you. You’re not broken; you’re finally grieving the whole story—not just the ending.

One of the great myths about grief is that it requires closure. It seems as though healing means shutting it away and moving forward unaffected. However, most people who grieve deeply will tell you the truth: it’s about integration. It’s about carrying it differently, not forgetting. With layered grief, each wave offers us another opportunity to confront parts of ourselves that we had to leave behind the first time. Grief opens doors to old rooms. If you find yourself feeling undone again—by a song, a scent, or a memory that shouldn’t hurt but does—it may indicate that another layer is seeking to be acknowledged. This doesn’t mean you’re falling apart; rather, it might suggest that you’re ready to grieve something you couldn’t before. That’s sacred. That’s progress, even if it feels like pain.

Grieving in layers is not a burden to carry. It’s a testament to how deeply you loved, how profoundly you remember, and how human you are. Each layer invites you to feel what’s true, to honor what was lost, and to reconnect with the parts of you that got left behind in the first wave.

Please take your time. Let the layers unfold. Grief has no expiration date. It will return, not to haunt you, but to heal you—one layer at a time.

Six Basic Truths About Sex by Claudia Six, PhD.

Every once in a while I tell my clients what I call ‘Basic Truths’ – stuff I don’t make up but that is inherently true. Here are a few of them:

If you want to be seen, you have to show yourself. Makes sense.

Similarly, if you want to be heard …you have to speak up!

If you make someone wrong, it’s because you got triggered. No matter how wrong they may or may not be, what happened is that your buttons got pushed. And that is what is relevant. Making others wrong is a defensive reaction.

When you defend you’ve already lost. You never need to defend yourself, except in a court of law. So when you defend yourself in everyday life, you’re essentially putting yourself one step down, and trying to elevate yourself back to the level of the other person.

People always give you information about themselves. When someone says “You’re too sensitive, you’re too thin”, they mean “You’re too sensitive for them! They’re telling you what they are comfortable with. They’re not giving you information about you. You’re just fine!

Erotic Integrity™ is a lifelong journey. Sexuality is not static. It evolves over the course of a lifetime, and people discover things about themselves at all ages. I love having clients in their seventies uncover new aspects of their eroticism, own it, and embrace it.

Claudia Six MA, PhD, Clinical Sexologist for over 30 years

Why Telling the Truth is the Hardest—and Most Loving—Thing You Can Do in Counseling

Why Telling the Truth is the Hardest—and Most Loving—Thing You Can Do in Counseling

When couples come into counseling, it’s not always because they’re ready to speak the truth. Often, it’s because the weight of not saying it has become unbearable. In her seminal book Tell Me No Lies, Dr. Ellyn Bader names something essential: we lie not just to deceive but to protect—ourselves, each other, and the fragile system we’ve built together. But over time, those protections become the very thing that keeps real intimacy out.

One of the most common dynamics that Bader identifies is what she terms “Developmental Arrest,” when one or both partners halt their individual growth to maintain peace in the relationship. These are the couples who say, “We don’t fight,” yet haven’t been emotionally honest in years. In therapy, that silence often cracks open first—not with shouting, but with one partner whispering something they’ve never voiced before.

Couples in this space are invited to tolerate the tension of truth. That means recognizing how easy it is to sugarcoat, minimize, or defer out of fear of conflict or loss. But intimacy requires more than closeness—it necessitates differentiation, the ability to stand in your truth while remaining emotionally connected. It’s not about winning or being right; it’s about being genuine without distancing yourself.

Telling the truth also means allowing your partner to have their own experience without managing it for them. When one partner shares, “I’ve felt alone in this marriage for years,” the other’s task is not to defend, fix, or counterattack. Their task is to stay present. Bader teaches that couples who can do this are practicing what she calls emotional muscle-building: staying close to pain without shutting down or lashing out.

The hard part? Most of us were never taught how to navigate this. We enter relationships with coping strategies developed in childhood—tools that helped us survive but now prevent us from being fully known. Tell Me No Lies reminds us that therapy is not just about mending what’s broken but transforming how we connect. What is true for you, once articulated, changes the atmosphere. The air becomes more breathable—even if heavier—temporarily.

Progress doesn’t always look like harmony. Sometimes, it looks like messy, raw, uncomfortable honesty. But couples who walk through that fire together often find something more profound on the other side—not just reconciliation, but revelation. Not just a return to love but a reinvention of it. “When you accept the troubles you have been given, a door opens.” —-Rumi

It Is Not a Secret: What You Notice Is Not What You Summon Part — 2 of 2 by Don Elium MFT

It Is No Secret:

What You Notice Is Not What You Summon

Part 2

by Don Elium MFT

Few ideas have spread faster—or sunk in deeper—than the belief that what you focus on creates reality. The self-help market has been built on this promise: think hard enough, feel deeply enough, and you’ll bring it into being. Love. Money. Healing. It’s not just wishful thinking—it’s the “law of attraction.” It sounds like physics. It feels like truth.

But looking at it from a steadier place, something else comes into view.

Maybe it’s not power you’re being offered, but pressure. Perhaps it’s not freedom but a subtle kind of blame. For people living with chronic pain, irreversible loss, or situations that the culture doesn’t even have a language for—this framing can complicate everything. It doesn't just miss the mark. It can quietly cut.

What if your thoughts don’t control the universe? What if they don’t summon events from the void?

What if what they really do is shape what you notice?

That’s not magic. That’s neurobiology.

When you focus on something—say, red cars—you begin to see them everywhere. Not because you conjured them but because your brain has flagged them as relevant. It’s called the reticular activating system—a built-in attentional filter. It helps determine what stands out and what fades into the background.

There’s also something called the Baader-Meinhof phenomenon or frequency illusion. Once something is named in your awareness, it seems to multiply. Not because it’s suddenly everywhere but because you are now tuned in. That difference—between noticing and creating—is everything.

Because if you believe your thoughts create reality, then every diagnosis, heartbreak, or failure starts to look like your fault. You didn’t stay “high vibe.” You let fear slip in. Your suffering becomes evidence that you failed to do it right.

That’s the quiet sadness at the core of magical thinking. It tells you healing is possible—but only if you think the right thoughts, feel the right feelings, or vibrate at the right frequency. If things fall apart, well, maybe you blocked your own blessings.

But that’s not how the brain works.

And it’s not how life works.

What you focus on doesn’t shape what exists. It shapes what appears to you.

Focus doesn’t control outcomes. It controls awareness.

It shifts the lens, not the landscape.

And still—something mysterious happens.

There are moments when your internal world seems to meet the outer one in perfect timing.

You think of someone and the phone rings.

A word repeats in your head, then shows up in a song, a headline, a stranger’s mouth.

These moments are real. But they’re not proof of a vending machine universe.

They’re proof that you’re alive and connected.

They aren’t evidence of summoning.

They’re resonance.

These are moments when attention and timing harmonize—not caused. Aligned.

They feel electric because they are—lighting up the circuits of memory and meaning in your nervous system.

Not because you made them happen. But because you were present enough to notice when they did.

It Is No Secret: Reclaiming Your Attention from Magical Thinking — Part 1 of 2

It Is No Secret:

Reclaiming Your Attention From Magical Thinking

Part 1 of 2

By Don Elium MFT