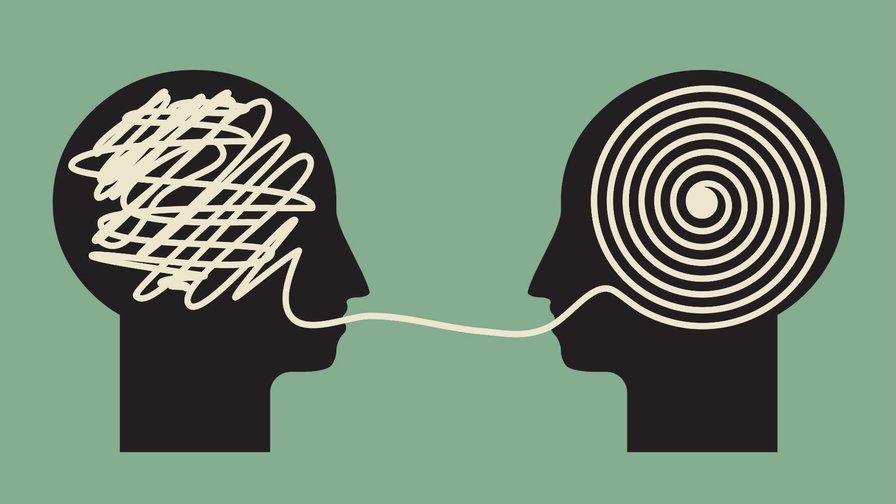

In marriages and family relationships, strong emotions can broadly fall into two categories: hot emotions, such as anger or frustration, and cold emotions, like detachment or indifference. When these tones dominate conversations, they often convey a more profound, unintended message of hate and apathy— instead what is happening which is an overwhelming cry for help.

The Nature of Hot Emotions

Hot emotions, marked by fiery anger, frustration, or even rage, erupt when someone feels overwhelmed, unheard, or disrespected. These emotions often act as a pressure valve for underlying issues, such as unmet needs, perceived injustices, or unaddressed vulnerabilities.

Imagine a spouse snapping at their partner over a seemingly minor issue, like leaving dishes in the sink. The anger may not be about the dishes but rather an unmet need for shared responsibility or feeling valued in the relationship. What is behind the unintended message of criticism, hardness and anger might be: “I feel overwhelmed,” or “I need help and connection.”

While hot emotions grab attention, their intensity can overshadow the underlying cry for help, leading the recipient to focus on the anger rather than the reason behind it. This often results in defensiveness, further escalating the situation.

The Nature of Cold Emotions

Cold emotions, on the other hand, manifest as detachment, withdrawal, or a chilling indifference. These arise when someone feels overwhelmed, hopeless, or resigned—when expressing hot emotions no longer feels viable.

Consider a parent who seems distant and unresponsive to their child’s questions. While the behavior might appear cold or dismissive, the underlying cry for help could be: “I’m exhausted,” or “I’m struggling to cope.” Cold emotions often mask a profound need for support, connection, or relief.

Unfortunately, cold emotions can be as damaging as hot ones, fostering misunderstandings and a sense of rejection. They send the unintended message that the individual no longer cares, even when the opposite may be true.

The Danger of Misinterpreting Emotions

In the heat of the moment, it’s easy to misinterpret the expression of hot or cold emotions as hostility, rejection, or apathy. This can perpetuate a cycle of conflict or disconnection, as the underlying needs and vulnerabilities go unaddressed. When the true message—“I need help” or “I’m struggling”—remains unheard, relationships can suffer deeply.

How to Respond to the Cry for Help

Breaking this cycle requires intentionality and empathy. Here are some strategies to navigate these emotionally charged situations:

Pause and Reflect: Instead of reacting to the surface emotion, take a moment to consider what might be driving it. Ask yourself, “What is my partner or family member truly trying to communicate?”

Acknowledge the Emotion: Validate the emotion being expressed, even if it’s difficult to hear. For example, “I can see that you’re really upset,” or “I notice you’ve been quieter than usual.”

Ask Open-Ended Questions: Create space for deeper conversation by asking questions like, “What’s been on your mind?” or “How can I support you?”

Cultivate Emotional Safety by responding without judgment or defensiveness. This builds trust and makes it easier for others to share their vulnerabilities.

Seek Professional Help When Needed: Persistent patterns of hot or cold emotions may benefit from the guidance of a therapist or counselor. They can help uncover and address the underlying issues more effectively.

Therefore:

Hot and cold emotions, while seemingly opposite, both signal that something deeper needs attention. Before the intensity gets hot or cold, there is an intent: please listen and understand what I need you to know about me and this situation. When that message is not received with compassionate curiosity, hot and cold intensity sends an unintended message of hate you or I don’t care about you.

In marital and family relationships, recognizing these emotions as cries for help can shift the dynamic from conflict or disconnection to: understanding and reasonable actions to address the needs. Where past hot and cold episodes have caused deep resentment, refocusing and hearing the original intended message can bring a healing opportunity.

By tuning in to the underlying needs and responding with empathy, families can create a space where vulnerability is met with support rather than misunderstanding. In doing so, they address the immediate emotional expression and strengthen the bonds that hold them together.