The Early Stages of Love: Chemistry at Play

The saying "love is blind" captures a profound truth about romantic relationships: intense feelings of love and attraction can often obscure our ability to see or acknowledge a partner's flaws. This phenomenon is particularly evident in the early stages of a relationship, where idealization and emotional highs can create a temporary veil over reality. However, as relationships mature, this initial blindness can evolve into a deep, enduring love marked by compassion, consideration, intention, and commitment.

Idealization of the Partner

In the excitement of new love, individuals often engage in romantic idealization, focusing on their partner’s positive traits while overlooking any flaws. This idealization is fueled by the novelty of the relationship and the intense emotional connections being formed. People may also project their own desires and values onto their partners, interpreting behaviors through the lens of their expectations rather than recognizing underlying issues.

Emotional Highs

The initial stages of love are characterized by the release of neurochemicals like dopamine and oxytocin. Dopamine, often dubbed the "feel-good" neurotransmitter, heightens feelings of euphoria and pleasure, encouraging individuals to focus on the positives in their partners. Oxytocin, known as the "bonding hormone," is released during physical intimacy, fostering feelings of closeness and attachment. These neurochemical responses contribute to a heightened emotional state that can cloud judgment, leading to an uncritical view of a partner.

The Rational Blindness and Bonding of Orgasm

During orgasm, the brain’s lateral orbitofrontal cortex and prefrontal cortex, areas responsible for rational thinking, self-control, and critical judgment, temporarily deactivate, creating a state of reduced inhibition and heightened emotional and physical sensation. Simultaneously, the brain floods with oxytocin and dopamine, hormones associated with bonding and pleasure, which enhance feelings of love and connection. This neurochemical cocktail, paired with the suppression of fear and judgment (reduced amygdala activity), can make love feel all-encompassing and overwhelming, effectively “blinding” you to rational concerns or potential flaws in your partner, reinforcing intimacy and connection.

Fear of Loss

The desire for connection can create a fear of loss, prompting individuals to avoid addressing potential conflicts. In the early stages of a relationship, the instinct to maintain harmony often takes precedence over confronting issues. This desire to sustain emotional closeness can lead partners to overlook red flags, believing that love alone will resolve any problems.

Transition to Compassion and Consideration

As relationships progress, the initial blindness can transform into a more nuanced understanding of one another, driven by intention and commitment.

Growth Through Experience

As partners navigate the challenges that arise in their relationship, they are often required to confront each other's complexities. This journey fosters deeper understanding and empathy, as they learn to appreciate one another’s struggles. Recognizing that everyone has imperfections allows for a more realistic and compassionate view of the relationship.

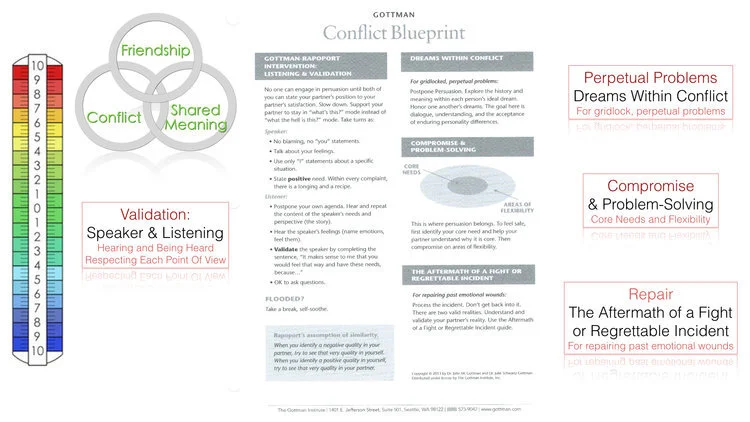

Communication and Vulnerability

With the establishment of trust, partners may begin to share their vulnerabilities and concerns openly. Honest communication enables them to address issues constructively rather than avoiding them. As they actively support each other through challenges, a sense of teamwork and resilience develops, further deepening their bond.

Building Resilience

Overcoming difficulties together strengthens the connection between partners. The process of addressing and resolving conflicts cultivates solidarity, reinforcing their commitment to one another. As love matures, partners often learn to accept each other's imperfections, rooted in a deeper understanding of what it means to be human.

The Biological Basis of Forever Love

Dr. Mary Fridman O'Connor, in her book "The Grieving Brain," explores the emotional and biological chemistry that underpins deep, enduring connections—what she refers to as the Forever Bond. This bond is shaped by several key biochemical and neurological factors:

Neurotransmitters and Hormones

- Oxytocin: Released during physical touch and intimacy, oxytocin promotes feelings of closeness and trust, reinforcing emotional bonds.

- Vasopressin: Similar to oxytocin, vasopressin is linked to protective behaviors and commitment, contributing to the stability of long-term relationships.

- Dopamine: This neurotransmitter enhances feelings of pleasure and motivation, crucial for establishing and maintaining attraction.

- Serotonin: Regulating mood, stable serotonin levels contribute to emotional balance and well-being, essential for a healthy Forever Bond.

Brain Regions Involved

- The Limbic System: Responsible for processing emotions and forming memories, the limbic system fosters emotional connections that reinforce the Forever Bond during moments of love and attachment.

- The Prefrontal Cortex: This area of the brain is involved in decision-making and rational thought. A healthy balance in prefrontal cortex activity allows individuals to navigate the complexities of relationships, fostering understanding and compassion.

The Role of Intention and Commitment

While chemistry plays a critical role in the formation of love, intention and commitment are equally vital. Partners who approach their relationship with a conscious intention to understand, support, and grow together create a fertile ground for compassion and consideration. Commitment provides a sense of security and stability, allowing both partners to navigate challenges with resilience.

Therefore

Initially, love can create a blindness to a partner's issues due to idealization, emotional highs, and the desire for connection. However, as relationships evolve and partners face challenges together, this blindness can transform into compassion and consideration. The interplay of biological chemistry, intention, and commitment is essential for developing a mature and enduring love—one where both partners feel seen, understood, and supported in their complexities. The journey from blind love to a lasting Forever Bond is not just about overcoming obstacles; it's about nurturing a deep connection that thrives on empathy, communication, and resilience.